A Bloody Mass

M.A.M. Huson 1,2, R.A.S. Hoek 1, M. de Mendonça Melo 2, E. Vis 3, M. Hellemons 1

1. Department of pulmonology, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

2. Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

3. Department of Pulmonolgy, Admiraal de Ruyter Ziekenhuis, Goes, the Netherlands

Case

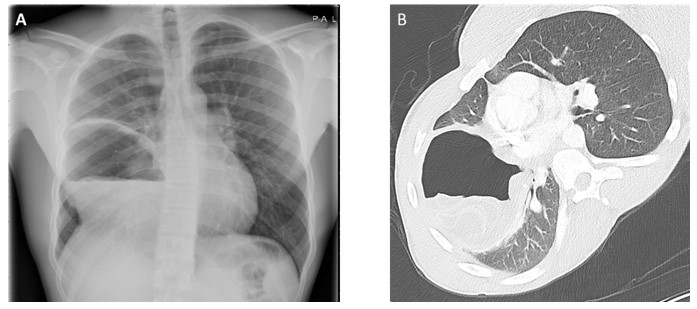

A 23 year old cook of Eritrean origin who lived in the Netherlands for 5 years presented with acute massive hemoptysis and hemodynamic collapse. He previously consulted his general practitioner for low-grade nagging thoracic pain in the right flank for 2 years that was slowly progressive. A previous chest X-ray reported a congenital diaphragmatic herniation.

On physical examination his respiratory rate was 24/min with an oxygen saturation of 94% on room air. His blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg with a regular pulse of 95 bpm and a temperature of 37.5°C. Laboratory revealed a CRP of 126 mg/L, a Hb of 13.5 g/dL, leukocytes of 7.6 x 10 9/L, with an absolute eosinophil count of 0.52 x 10 9/L. Renal and liver function were within normal limits. His HIV test was negative, as well as his Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA). Feces was PCR positive for Schistosoma spp.

Image 1: Chest X-ray (A), and CT chest (B)

Question

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Congenital pulmonary airway malformation

- Chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis

- Echinococcosis

- Ruptured congenital diaphragmatic hernia

- Schistosomiasis

- Tuberculosis

C. Echinococcosis

Discussion

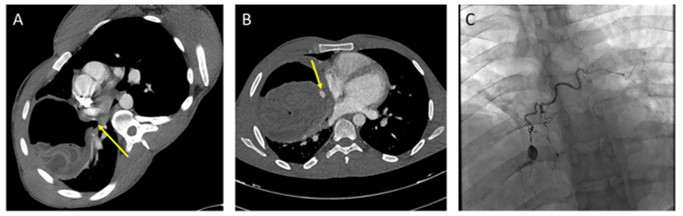

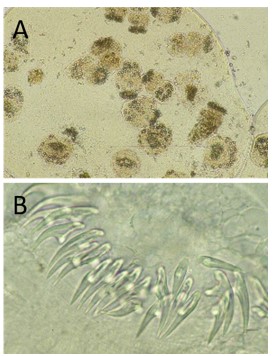

Answer C is the correct answer. This patient experienced hemoptysis and anaphylactic reaction due to a ruptured Echinococcus granulosus cyst. Serology for echinococcosis was negative, but does not rule out echinococcosis. On CT-scan there is an impression of a worm-like structure inside the cyst. These are the walls of daughter cysts described as the ‘water-lily sign’. Additional Images demonstrate connection with the middle lobe bronchus and encasement of a pseudoaneurysm connecting to the right bronchial artery (Image 2). Bronchoscopy revealed a large cavern with a necrotic wall. Microscopy of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid demonstrated a large number of protoscolices of E. granulosus (Image 3). Co-presence of liver cysts was excluded with abdominal ultrasound.

Infection with E. granulosus occurs worldwide. Prevalence is up to 5-10% in endemic areas, including East Africa (1). Infected dogs are the definitive host and harbor adult tapeworms in their intestines, shedding eggs in their feces. When eggs are ingested by susceptible herbivorous intermediate hosts, the oncospheres hatch, penetrate the intestinal wall, and enter the circulation to form hydatid cysts in the organs, predominantly liver and lungs. From the inner surface of the cyst, protoscolices develop (2). Humans become infected by accidentally ingesting eggs. Patients can be asymptomatic for years and echinococcal cysts are often an incidental finding by imaging. A significant proportion of cysts spontaneously stop growing and can be managed with watchful waiting (3). However, the presence of intact protoscoleces, as well as the ‘water-lily sign’ on imaging, in our patient is evidence of viability of the echinococcal cyst. Symptoms often arise after rupture of cysts (either spontaneously or due to trauma), which can cause anaphylactic reactions that range from mild to lethal anaphylactic shock (3). In pulmonary echinococcosis, complications can arise due to mass effect, and rupture into the bronchial artery, resulting in hemoptysis and anaphylaxis as observed in our patient.

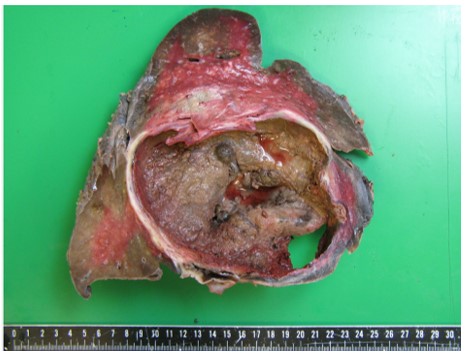

Co-infection with Schistosoma was present, but schistosomiasis usually results in hepato-splenic, intestinal, or urogenital disease. Lung involvement is described in the acute phase due to migrating larvae in the lungs, causing migrating eosinophilic pulmonary infiltrates known as Loeffler syndrome (1). Chronic cavitary aspergillosis (CCPA) can also cause large cystic lesions in the lung, which may result in hemoptysis. CCPA usually shows multiple cavities, which may or may not contain an aspergilloma, but are most frequently seen in the upper lobes in patients with underlying lung disease. Also, fungal cultures were negative in our patient. Tuberculosis may also form large cavernous lung lesions associated with hemoptysis and is highly endemic in Eritrea, but was excluded by repeated negative GeneXpert results for sputa and BAL. In case of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia, the CT scan would reveal intra-abdominal organs in the thoracic cavity. Congenital pulmonary airway malformations result from abnormalities of branching morphogenesis of the lung and can present with recurrent pneumonia, spontaneous pneumothorax or hemoptysis, but are rarely seen in adults. Our patient was started on albendazole 400mg BD and a single dose of praziquantel for concomitant Schistosoma infection. Due to progressive hemoptysis, embolization of the right bronchial artery was performed. Unfortunately, after an initial beneficial response, massive hemoptysis recurred, requiring emergency resection of the lung. Perioperatively extensive ingrowth in the mediastinum, diaphragm and vessels prohibited bilobectomy, so right pneumonectomy was performed (Image 4). Given the complex surgical procedure with spill into the thoracic cavity, the cavity was rinsed with protoscolicidal hypertonic saline (20% w/v) afterwards. Postoperatively praziquantel 60mg/kg OD was added to the albendazole treatment for a duration of 2 weeks, as it may prevent cyst dissemination by the vesicular development of released daughter cysts. Furthermore, combining praziquantel and albendazole increases albendazole concentrations in blood plasma and thereby probably in cyst fluid, which seems to improve outcome when spillage occurs during surgical procedure (5). Postoperative recovery was uneventful. The patient is currently still on albendazole treatment which will be continued for at least six months. He will be monitored for recurrent disease.

Image 2: On CTA in soft tissue window the water lilly sign is more clearly visible and a connection to the middle bronchus can be observed (arrow) (A). In addition CTA demonstrates a pseudoaneurysm encased by the echinococcal cyst (arrow) (B). Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) demonstrates more clearly the pseudoaneurysm connected to the right bronchial artery (C).

Image 3: Protoscolices of Echinococcus granulosus. Panel A shows an overview a multiple protoscolices, of which some are evaginated and others are not. Panel B shows an enlargement of the ring of rostellar hooks on evaginated protoscolices. Images were prepared by Rob Koelewijn, Dept. Medical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Image 4: Resected right lung revealing a large cystic mass.

References

-

WHO. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/echinococcosis

-

T N, Marti H, Duhnsen S, G B. Pulmonary schistosomiasis - imaging features. J Radiol Case Rep. 2010;4(9):37-43.

-

CDC. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/echinococcosis/biology.html

-

Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA, Writing Panel for the W-I. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114(1):1-16.

-

Velasco-Tirado V, Alonso-Sardon M, Lopez-Bernus A, Romero-Alegria A, Burguillo FJ, Muro A, et al. Medical treatment of cystic echinococcosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):306.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. J.J. van Hellemond, associate professor at the Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases at Erasmus Medical Centre, for his helpful comments and for providing the parasitology images and Dr. A. Odink, thoracic radiologist for her support providing the radiological images.