A Case of Two Siblings: Different or the Same?

Authors: Timothy Klouda, DO1, Kathryn Della Barba1, Kenan Haver, MD1

Institutes: Boston Children’s Hospital, Division of Pulmonary Medicine, Boston, MA 02115.

Case

A 14-year-old male, Patient A and his 9-year-old brother, Patient B, were referred to the pediatric pulmonary clinic for evaluation by their pediatrician.

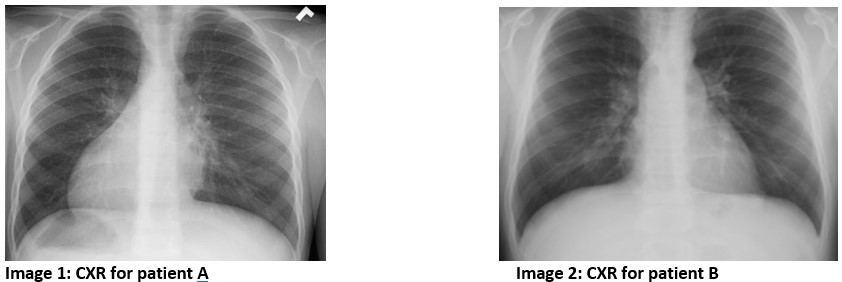

Patient A had a history of recurrent ear infections and eustachian tube dysfunction which has resolved since tympanostomy tube placement. On review of past medical history, it was noted that he was born at 39 weeks gestational age. At 36 hours of life he developed unexplained respiratory distress that required supplemental oxygen. A recent CXR is shown below in Figure 1.

Patient B had a history of year-round nasal congestion and a daily wet cough since birth. On review of past medical history, he was born full term without any complications and had no history of hospitalizations. A recent CXR can be seen below.

Question

Based on the above history and imaging, which patient requires further diagnostic testing for primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD)?

- Patient A

- Patient B

- Both

- Neither

C. Both

Discussion

The clinical history for both Patient A and Patient B is concerning for a diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). PCD is a genetic, autosomal recessive disorder characterized by defective ciliary structure and function.1

The diagnosis of PCD is challenging and typically relies on both clinical history and diagnostic testing including nasal nitric oxide (nNO), ciliary biopsy and genetic testing. Due to the variety of diagnostic tests available, referral to a specialty center which can provide a comprehensive evaluation and interpretation of tests is recommended. In 2018, the American Thoracic Society released Clinical Practice Guidelines which included a diagnostic algorithm for evaluating a patient with suspected PCD. The diagnostic criteria for primary ciliary dyskinesia include having two or more of the major criteria plus at least one of the minor criteria.4

Major criteria:

- Unexplained neonatal respiratory distress in term infant

- Year-round daily cough beginning before 6 months of age

- Year-round daily nasal congestion beginning before 6 months of age

- Organ laterality defect

Minor criteria:

- nNO during plateau <77 nL/min on 2 occasions, >2 months apart, with CF excluded

- Diagnostic ciliary ultrastructure on EM

- Biallelic mutations in one PCD gene

- Persistent and diagnostic ciliary waveform abnormalities on high-speed video-microscopy, on multiple occasions

Both patients above have two major criteria for PCD and should undergo further testing to evaluate for ciliary disease. While recurrent episodes of acute otitis media and sinusitis can be seen in patients with PCD and ciliopathies, currently it is not included as criteria in the diagnostic guidelines published by the ATS. Genetic testing is a key part of diagnosing PCD. There are currently 45 genes known to be associated with PCD, with the most common being DNAI1 and DNAH5, however approximately 20-30% of patients who fit the diagnostic criteria do not have an identified genetic variant.3 While heterotaxy and laterality defects can be seen in healthy, asymptomatic patients, their presence should prompt further investigation to determine if testing for PCD is warranted. Interestingly in the case above, while both siblings have PCD, only one has laterality defects (Patient A), highlighting the complex relationship between PCD, laterality defects and inheritance.

Nodal cilia, one of the three classes of cilia, are involved in determining left-right body orientation. Abnormalities in the motility of nodal cilia can result in laterality defects seen in approximately 50% of PCD patients.2 These can include both situs inversus totalis and situs ambiguous. Situs inversus totalis, which is seen in Figure 1, is the reversed lateralization of all visceral organs and present in 40-50% of PCD patients.3 Heterotaxy, or situs ambiguus, is characterized by the abnormal distribution, but not complete reversed lateralization, of visceral organs within the chest and abdomen and is seen in about 12% of PCD patients.3

Other organ systems can be affected in patients with heterotaxy, such as the spleen, and further evaluation for asplenia or polyspenia are warranted. There are, at this time, no therapies specifically approved for patients with PCD. Recommended therapies include airway clearance with nebulized hypertonic saline and chest physiotherapy, with the goal of preventing exacerbations and slowing disease progression.2

References

-

Kennedy MP, Omran H, Leigh MW, et al. Congenital Heart Disease and Other Heterotaxic Defects in a Large Cohort of Patients with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Circulation.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649038. Published May 21, 2007. -

Mirra V, Werner C, Santamaria F. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia: An Update on Clinical Aspects, Genetics, Diagnosis, and Future Treatment Strategies. Frontiers in Pediatrics.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28649564/. Published June 9, 2017. -

Maimoona ZA, Knowles MR, Leigh MW. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1122/. Published January 24, 2007. -

Diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia: An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Volume 197 Number 12 | June 15, 2018