A Tangled Case of Incidental Hypoxemia

Lena Xiao MD 1,2, Felix Ratjen MD PhD 1,2, Reshma Amin MD MSc 1,2

1Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

2University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Case

A seven-year-old previously healthy girl presented for an elective endoscopy to investigate for dysphagia and was incidentally found to have low baseline oxygen saturations of 91-94%. There was a longstanding history of exercise intolerance as well as 1-2 episodes of epistaxis monthly. There was no history of hemoptysis or recurrent respiratory infections. On examination, she was found to have facial telangiectasias and digital clubbing. Her bloodwork revealed polycythemia with hemoglobin 156 g/L (15.6 g/dL) and hematocrit 47.2%. Echocardiography was unremarkable. Chest x-ray revealed subtle ground-glass nodular opacities suspicious for an infectious process. Testing for mycoplasma, respiratory viruses, and COVID-19 were negative.

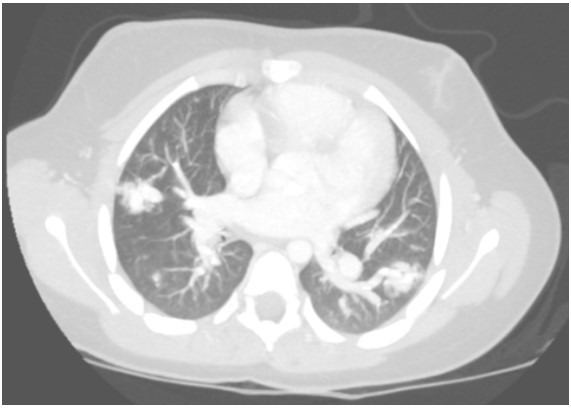

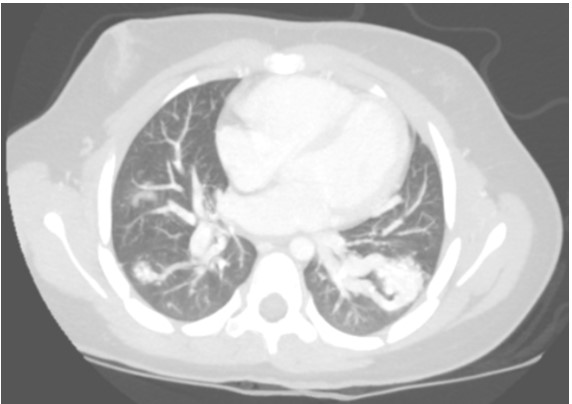

A contrast-enhanced CT with maximum-intensity projection reconstruction showed the following:

Question

What is the most likely cause of her hypoxemia?

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

- Tuberculosis

- Fanconi anemia

B. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

The CT with maximum-intensity projection reconstruction shows a total of three large pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMs) located in the right upper lobe, right lower lobe, and left lower lobe. The chest CT finding of a serpiginous mass or nodule with an enlarged feeding artery and one or more draining veins is diagnostic of a PAVM. The majority of PAVMs are associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). This patient also had telangiectasias and recurrent epistaxis that are characteristic of HHT.

The vascular malformation of hepatopulmonary syndrome (choice A) is characterized by portal hypertension and dilated pulmonary capillaries with macroscopic PAVMS being a rare finding. The diagnostic criteria for hepatopulmonary syndrome include liver disease, arterial blood gas demonstrating partial pressure of oxygen < 70 mmHg or alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient ≥ 15 mmHg on ambient air, and evidence of pulmonary vascular dilatation. Hepatopulmonary syndrome should be suspected in patients with hypoxemia and known hepatic disease. PAVMs have also been reported in association with tuberculosis (choice C) and Fanconi anemia (choice D) but are unlikely in this scenario without any other suggestive symptoms. Mycobacterium tuberculosis may be considered in the setting of PAVMs when there is a history of active or remote pulmonary tuberculosis or patient risk factors for tuberculosis. However, a causal relationship between tuberculosis and PAVMs has not been established. Fanconi anemia is a multisystem, genetic disorder characterized by progressive bone marrow failure and multiple congenital anomalies. It has rarely been associated with cardiovascular abnormalities including PAVMs.

Discussion

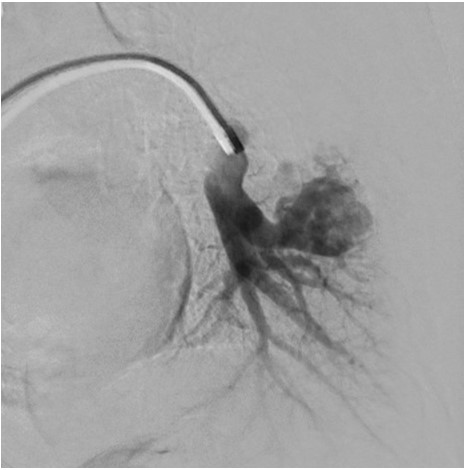

Further history revealed a positive family history for HHT on the paternal side. Manifestations in the father included recurrent spontaneous epistaxis and facial telangiectasias. Genetic testing in the patient was positive for a partial deletion of exons 4 to 8 in the endoglin gene, confirming a diagnosis of HHT.A screening brain MRI for cerebral vascular malformations was unremarkable. She underwent embolization of all three PAVMs and her baseline oxygen saturations improved to 98% on room air.

Pulmonary angiography demonstrating left lower lobe PAVM.

PAVMs are abnormal vascular structures characterized by the direct connection of a pulmonary artery and vein without an intervening capillary, thereby creating an intrapulmonary right to left shunt. The classic clinical triad of dyspnea, clubbing, and cyanosis is seen in a minority of patients. The gold standard method for diagnosing PAVMs is pulmonary angiography. Large or symptomatic PAVMs should be embolized to prevent serious complications such as cerebral thrombosis, cerebral abscess, massive hemoptysis, and spontaneous hemothorax.1 Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for procedures associated with bacteremia (eg dental procedures) due to the risk of cerebral abscess. Additionally, extra care should be taken to avoid intravenous air bubbles through the use of an in-line intravenous filter to prevent cerebral air embolism.

HHT, also known as Rendu-Osler-Weber Syndrome, is the underlying disease in the majority of adults and children with PAVMs. HHT is an autosomal dominant disorder with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 5000.2 It is characterized by vascular malformations in the skin, nasopharynx, brain, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs. If left untreated, vascular malformations may give rise to catastrophic complications such as life-threatening hemorrhage. HHT can be diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria or confirmed genetic testing. Mutations in two major genes affecting the transforming growth factor beta pathway, the endoglin gene and the activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene, account for the majority of HHT cases.3 A diagnosis of HHT is considered definite if 3 or more of the following clinical criteria are present, possible with 2 criteria present, and unlikely if 1 or 0 criteria is positive.4

Clinical HHT criteria:4

- Epistaxis: spontaneous, recurrent nose bleeds

- Telangiectasias: multiple, at characteristic sites (lips, oral cavity, fingers, nose)

- Visceral lesions such as gastrointestinal telangiectasia, PAVM, hepatic arteriovenous malformation, cerebral arteriovenous malformation, or spinal arteriovenous malformations

- Family history: a first degree relative with HHT according to these criteria

International HHT Guidelines recommend that asymptomatic children with HHT or those at risk for HHT should undergo screening for PAVMs and cerebral vascular malformations at the time of presentation.1 PAVM screening can be completed with transthoracic contrast echocardiography which has 100 % sensitivity for PAVMs.5

HHT is an underrecognized, multisystem vascular disease with variable penetrance and age-related expression. Clinicians must have a high index of suspicion for HHT when a PAVM is diagnosed and consider further diagnostic and screening investigations.

References

-

Faughnan ME, Mager JJ, Hetts SW, et al. Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):989-1001. doi:10.7326/M20-1443

-

Dakeishi M, Shioya T, Wada Y, et al. Genetic epidemiology of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in a local community in the northern part of Japan. Hum Mutat. 2002;19(2):140-148. doi:10.1002/humu.10026

-

Abdalla SA. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: current views on genetics and mechanisms of disease. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2005;43(2):97-110. doi:10.1136/jmg.2005.030833

-

Shovlin C, Guttmacher A, Buscarini E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Am J Med Genet. 2000;91(1):66-67.

-

Al-Saleh S, Dragulescu A, Manson D, et al. Utility of Contrast Echocardiography for Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformation Screening in Pediatric Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;160(6):1039-1043.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.11.038