All Good Things Must Come to an End

Authors: Swati Jayaram, Lisa Ulrich, Melissa Holtzlander

Department of Pediatric Pulmonology, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio

Case

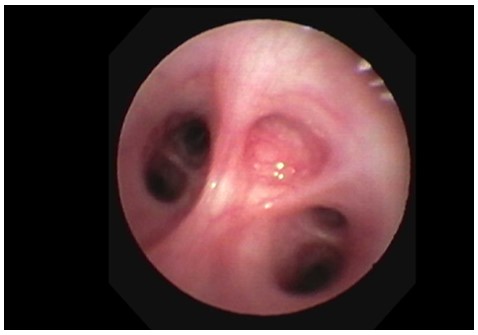

An 11 yo male with history of autism was seen in the emergency department for complaints of nausea, vomiting and a 30 lb weight loss over the past 2 months. Chest CT imaging was obtained by the emergency department for suspicion of malignancy. He was referred to the pulmonary clinic for significant CT imaging findings (Figure 1). Patient had chronic cough and shortness of breath for approximately 1 year, for which he was prescribed albuterol without a spacer. There were no prior episodes of pneumonia. Family history was significant for asthma. On examination there was no digital clubbing noted and auscultation revealed good aeration bilaterally without any adventious sounds. He was discharged with instructions to use albuterol with spacer and plans for combined endoscopy with both flexible bronchoscopy and GI endoscopy. On EGD, pyloric stricture was noted and dilated. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed the following findings in the lateral segment of right lower lobe (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Axial segments of Chest CT

Figure 2: Image of flexible bronchoscopy showing all the segments of right lower lobe

Question

What is the diagnosis?

- Congenital pulmonary airway malformation

- Bronchial atresia

- Pulmonary sequestration

- Mucoid impaction

Answer B. Bronchial Atresia

Discussion

Bronchial atresia is a rare congenital anomaly caused by focal interruption of a lobar, segmental or subsegmental bronchus. The exact pathogenesis of bronchial atresia remains unknown but there are two hypotheses which exist. One theory state that bronchial atresia is a result of vascular injury that occurs during early fetal development. The second postulates that it occurs due to the separation of the developing bronchial bud during normal lung maturation1.

Often, bronchial atresia is an incidental finding and patients are usually asymptomatic. One-third of patients report symptoms of cough, shortness of breath and recurrent infections and to a lesser extent wheezing, hemoptysis, chest pain, or pneumothorax2,3. In our patient, chronic cough and weight loss was likely secondary to pyloric stricture causing vomiting with subsequent aspiration of gastric contents. At his two-month follow-up after pylorus dilation, he had no symptoms of lingering cough.

Chest Xray usually shows nonspecific findings in bronchial atresia. Although upon careful examination, findings of an elongated opacity with focus of hyperinflation may increase your suspicion for bronchial atresia should be higher. Chest CT is more specific for the diagnosis of bronchial atresia. Usually, mucoceles and area of hyperinflation distal to the affected segment are what is seen. Rarely, if there is no mucoid impaction, an air-filled bronchus is visualized. This was the case in our patient, where the distal lung supplied by the atretic segment appeared hyperlucent secondary to air trapping and reduced pulmonary blood volume. Hyperinflation is typically present because of collateral ventilation through the bronchoalveolar channels of Lambert, pores of Kohn, or interbronchiolar channels4. Flexible bronchoscopy is another modality through which diagnosis of bronchial atresia can be made, which reveals a blind ending bronchus.

The management of bronchial atresia remains controversial. For patients who are asymptomatic, no active treatment is indicated. However, in patients who have recurrent infections and significant shortness of breath, surgical intervention is sought. While radiographic findings are essential for identifying patients who may have bronchial atresia, bronchoscopy confirmation should always be attempted to rule out other possible etiologies for segmental hyperinflation5.

Chest radiographs in CPAM usually demonstrates obvious multi-cystic air-filled lesions (Answer A is incorrect). In pulmonary sequestration, Chest CT demonstrates typical appearance of complex mass with or without cystic changes. This mass can be fluid or air filled microcysts or as a large cavitating lesion with an air fluid level (Answer C is incorrect). Whereas in Mucocele or mucoid impaction, imaging demonstrates classic “finger in glove” appearance from formation of mucoid in the distal bronchus (Answer D is incorrect).

References

-

Berrocal T, Madrid C, Novo S, Gutiérrez J, Arjonilla A, Gómez-León N. Congenital anomalies of the tracheobronchial tree, lung, and mediastinum: embryology, radiology, and pathology. 2004 Jan-Feb;24(1):e17

-

Wang Y, Dai W, Sun Y, Chu X, Yang B, Zhao M. Congenital bronchial atresia: diagnosis and treatment. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(3):207-12.

-

Psathakis K, Eleftheriou D, Boulas P, Mermigkis C, Tsintiris K. Congenital bronchial atresia presenting as a cavitary lesion on chest radiography: a case report. Cases J. 2009 Jan 07;2(1):17

-

de Melo ASA. Diagnostic imaging in bronchial atresia. Radiol Bras. 2021 Mar-Apr;54(2): V. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2021.54.2e1. PMID: 33854270; PMCID: PMC8029932.

-

Mahajan AK, Rahimi R, Vanderlaan P, Folch E, Gangadharan S, et al. (2017) Unique Approach to Diagnosing and Treating Congenital Bronchial Atresia (CBA): A Case Series. J Pulm Respir Med 7: 402. doi: 10.4172/2161-105X.100040