Lots of Lung Nodules

Avraham Z. Cooper, MD1, Jennifer W. McCallister, MD2, and Namita Sood, MD3.

1Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine Fellow, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH.

2Associate Clinical Professor in the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, & Sleep Medicine and Program Director of the Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Fellowship, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH.

3Professor of Critical Care, Pulmonary & Sleep Medicine and Director of the Pulmonary Vascular Disease Program, University of Texas, McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX.

Case

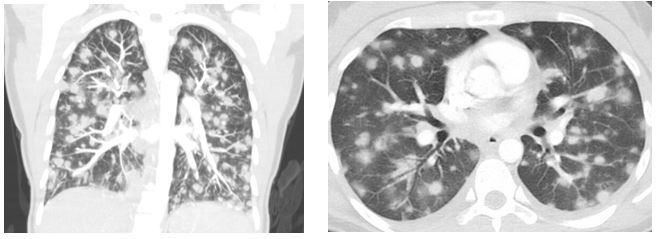

A 25-year-old woman without significant past medical history presented with three weeks of progressive dyspnea, productive cough, fevers, generalized fatigue, and malaise. She lived in a rural area in the Midwest and was a non-smoker. She denied weight loss, night-sweats, rash, or joint pain or swelling. Three weeks prior to presentation she was exposed to a large amount of dust during the Fall harvest on a vegetable farm. She did not have any other exposures. Chest examination revealed bilateral inspiratory rhonchi. Labs were notable for mild transaminitis, an elevated C-reactive protein to 108 mg/L, with normal complete blood count and serum chemistry panels, as well as negative antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Representative CT scan images of the chest are shown below (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Question

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Metastatic malignancy

- Pulmonary vasculitis

- Severe fungal infection

C. Severe fungal infection (acute diffuse pulmonary histoplasmosis)

Discussion

The patient’s clinical presentation was consistent with acute diffuse pulmonary histoplasmosis, a form of histoplasmosis that occurs after a large inhalational inoculum to fungal conidia. It manifests with diffuse pulmonary nodular (as seen in this patient) or micro-nodular infiltrates which eventually calcify (1). Exposure to large amounts of bird or bat droppings, such as from chicken coops or demolition sites, represent common sources of infection. This patient’s exposure likely occurred when inhaling soil particles during a field harvest three weeks prior to presentation. Pulmonary symptoms are often dependent on the degree of inhalational exposure, with severely affected patients potentially progressing to respiratory failure.

A positive result on histoplasma-specific antibody or antigen testing, in the appropriate clinical context, is usually diagnostic for acute infection. Histoplasma antigen can be detected in blood, urine, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid during acute infection and has a sensitivity of 64-82% (2). Complement fixing antibodies to mycelial and yeast antigens, as well as immunodiffusion antibodies (reported as an H or M band), are often positive in acute infection, though can take up to a month after the initial exposure to become positive, with titers rising over the next several weeks. A combined approach involving antigen and serologic assessment, in addition to tissue culture when available, is recommended and yields a diagnostic sensitivity of 96% (3).

Treatment with antifungal medications depends on the severity of illness and acute diffuse pulmonary histoplasmosis is often self-limited. According to recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America patients with mild or even moderate symptoms can be monitored without therapy, if symptoms have been present for less than a month. If symptoms have been present for longer than that time then at least six weeks of itraconazole treatment should be used. Patients with severe symptoms (e.g. respiratory failure) should be treated with amphotericin and corticosteroids initially and then receive itraconazole to complete a 12 week treatment course. Most patients recover completely though there is a risk for progression to chronic fibrotic lung disease or subsequent development of fibrosing mediastinitis; whether or not treatment with antifungals reduces these risks is not known (4).

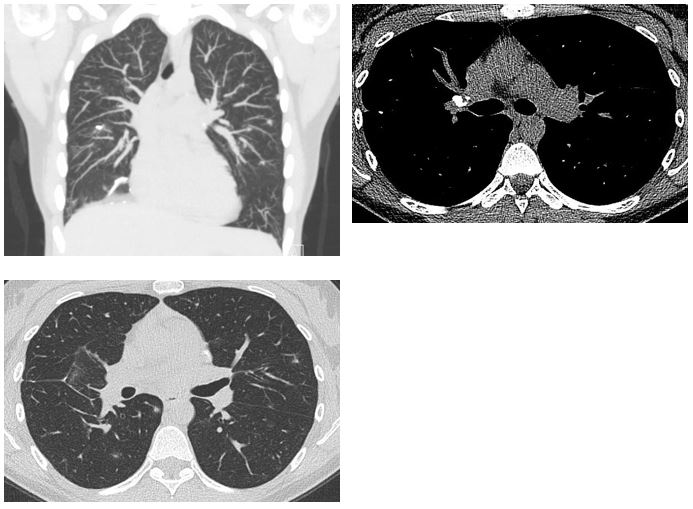

In this patient’s case, all work-up for histoplasmosis was initially negative aside from the histoplasma yeast complement fixation antibody, which returned positive at a 1:16 titer. Because of her recent environmental exposure, her otherwise negative infectious, inflammatory, and malignancy evaluation, and a detectable histoplasma titer it was felt that acute diffuse pulmonary histoplasmosis was the most likely diagnosis. Given the degree of parenchymal involvement and the length of time for which she was symptomatic she was initiated on treatment with six weeks of itraconazole. At follow-up she was asymptomatic. An interval CT scan acquired eight weeks after her initial presentation showed significant improvement in the size and burden of pulmonary nodules. Many of the residual nodules, as well as hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes, had developed calcifications, consistent with a resolving granulomatous process due to histoplasmosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2

References

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: A Clinical and Laboratory Update. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2007; 20(1): 115-32.

- Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, et. al. Diagnosis of Acute Pulmonary Histoplasmosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009; 49(12): 1878–82.

- Richer SM, Smedema ML, Durkin MM, et al. Improved Diagnosis of Acute Pulmonary Histoplasmosis by Combining Antigen and Antibody Detection. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2016; 62(7): 896-902.

- Wheat JL, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Histoplasmosis: 2007 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007; 45(7): 807–25.