Missed Connections

Daniel Galvan MD, Rissa Zudekoff MD, Nina Thomas MD

Case

A 70-year-old woman with a past medical history of ascending aortic aneurysm status post thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), deep venous thrombosis (DVT) on xarelto, and opioid use disorder on methadone presented to the emergency department complaining of gradually worsening chest pain and shortness of breath for the last 2 days.

On arrival, she was febrile to 39.3, tachycardic to a heart rate of 101, and hypotensive with a mean arterial pressure of 57. She received fluids, broad spectrum antibiotics, and was admitted to the MICU for presumed septic shock requiring norepinephrine and vasopressin. Blood cultures were collected and grew several organisms including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus salivarius, and Streptococcus mitis/oralis. She was started on broad spectrum antibiotics and cultures were repeated 48 hours after the initial cultures.

The second set of cultures continued to grow Staphylococcus aureus.

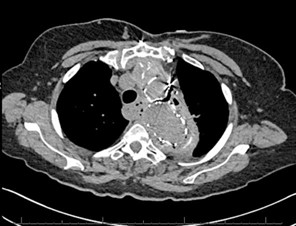

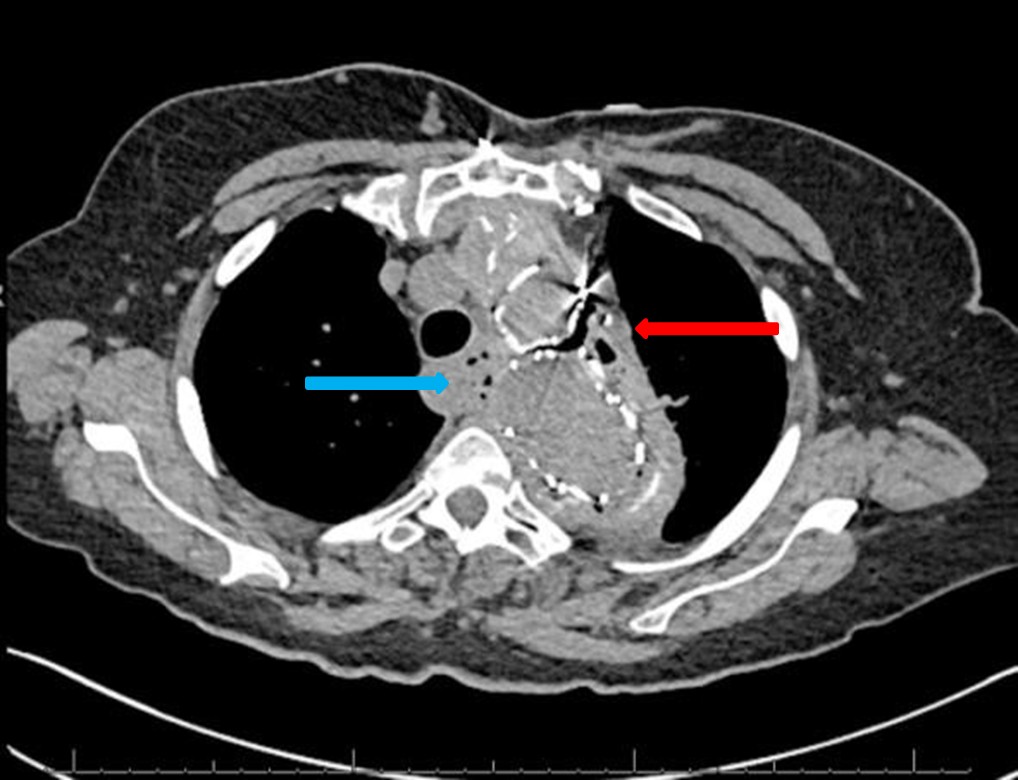

Chest CT was obtained and showed the following:

An esophagram was performed and showed the following:

Question

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

- Aortic dissection

- Infectious aortitis

- Aortoesophageal fistula

- Meckel’s diverticulum

C. Aortoesophageal fistula

Discussion

The chest CT demonstrated the thoracic aorta endograft repair with a moderate amount of air within the excluded aneurysm sac concerning for graft infection or fistula (red arrow, figure 1). There is also gas adjacent to the esophagus and loss of fat planes between the esophagus and the aneurysm sac (blue arrow, figure 1).

The esophagram demonstrated a contained esophageal leak originating at the level of the aortic arch (yellow arrow, figure 2). Given imaging findings and polymicrobial blood cultures, it suggests an esophageal fistula to the excluded aortic aneurysm. Although infectious aortitis could present similarly, one organism is typically isolated, and infectious aortitis would not explain the leak seen on the esophagram. In an aortic dissection, an intimal flap and false lumen would be seen on a CTA. Lastly, Meckel’s diverticulum is a small intestinal diverticulum that results from the vitelline duct failing to obliterate during development.

An aortoenteric fistula is a condition with a high mortality rate that arises from a fistula developing between the aorta and any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. Aortoenteric fistulas are classified as either primary or secondary aortoenteric fistulas. Primary aortoenteric fistulas occur with a native aorta while secondary arotoenteric fistulas occur from surgical interventions on the aorta or esophagus. Primary aortoenteric fistulas are commonly caused by atherosclerotic thoracic aortic aneurysms, mycotic aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms, and carcinoma of the esophagus. The most common causes of secondary aortoenteric fistulas include grafts and stents after the repair of a thoracic aneurysm or after esophageal surgery.

Aortoesophageal fistulas are a subtype with a fistula between the aorta and esophagus. Chiari’s triad has been used to describe the classical presentation of an aortoesophageal fistula defined as a triad of midthoracic pain, sentinel arterial hemorrhage, and exsanguination after a symptom-free interval. However, diagnosis is typically made at the time of massive hematemesis. In some rare instances, patients have presented with isolated sepsis, septic embolism to lower extremity, dysphagia, and/or chest pain.

In patients that are stable and do not require immediate surgery, diagnosis can be guided by different imaging modalities. Esophageal contrast studies including CT of the neck with oral contrast or an esophagram can show evidence of contrast material around the aortic prosthesis or demonstrate a complete esophageal perforation. CT can also show visualization of gas either around the prosthesis or inside an aneurysm. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) can be utilized to directly visualize the esophageal defect but some argue against its use due to the increased risk of worsening the perforation and fistula leading to fatal hemorrhage. The management of aortoesophageal fistulas typically requires a multimodal approach including surgical and non-surgical interventions. However, they still carry a poor prognosis with a high mortality rate.

Our patient presented with a rare case of an esophagoparaprosthetic fistula as a complication of a TEVAR diagnosed with CT imaging and an esophagram, which lead to polymicrobial septic shock. Ultimately, many specialists were involved including GI therapeutics, infectious disease, vascular, and cardiothoracic surgery though the surgical specialties were unable to offer further interventions. GI therapeutics did attempt to place an esophageal stent, though were unsuccessful due to lack of visualization of the fistula and concerns for risk of worsening perforation. Our patient was treated medically with a prolonged course of IV antibiotics. Given her unfortunate situation and limited options, there were extensive goal of care discussions, and she transitioned to hospice care. Intensivists should be familiar with this rare complication with a high mortality rate and should always keep it in their differential in a patient presenting with polymicrobial sepsis and a history of a TEVAR. Although it has a high mortality rate, a quicker diagnosis and involvement of multidisciplinary teams offers the best recourse for patients.

References

- Carter, R., Mulder, G. A., Snyder, E. N., & Brewer, L. A. (1978). Aortoesophageal fistula. The American Journal of Surgery, 136(1), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002- 9610(78)90195-2

- da Silva, E. S., Tozzi, F. L., Otochi, J. P., de Tolosa, E. M., Neves, C. R., & Fortes, F. (1999). Aortoesophageal fistula caused by aneurysm of the thoracic aorta: Successful surgical treatment, Case report, and literature review. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 30(6), 1150– 1157. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70056-x

- Hollander, J. E., & Quick, G. (1991). Aortoesophageal fistula: A comprehensive review of the literature. The American Journal of Medicine, 91(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(91)90129-l

- Kieffer, E., Chiche, L., & Gomes, D. (2003). Aortoesophageal fistula. Annals of Surgery, 238(2), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000080828.37493.e0

- Pipinos, I. I., & Reddy, D. J. (1997). Secondary aortoesophageal fistula. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 26(1), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70160-5