Progressive Life-Long Dyspnea

Michael Armstrong1, Anupam Banerjee2, Shawn P.E. Nishi MD3

1Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine- Virginia Campus, Blacksburg, VA

2University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX

3Division of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX

Case

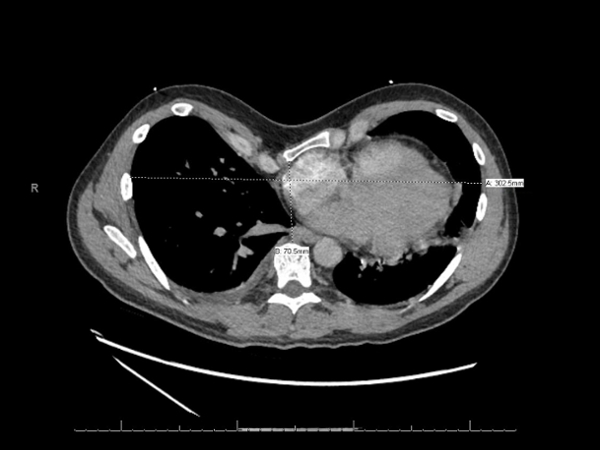

A 35-year-old male with a history of anxiety and depression presents to the office with a gradual onset of worsening dyspnea on exertion and decreased exercise tolerance. He has had trouble with this since his teenage years, but has noted significant progression over the past 1-2 years, now associated with trouble with endurance. His symptoms are not present at rest and he denies any cough, chest pain, or pleurisy. Further history and physical exam led to obtaining CT imaging, which is shown below:

Question

What is the diagnosis causing his shortness of breath?

- Blunt trauma to the chest

- Pectus carinatum

- Pectus excavatum

- Flail chest

Answer: C. Pectus Excavatum - The CT shows a concave chest wall deformity with cardiac displacement, most consistent with pectus excavatum (PE).

Discussion

Pectus excavatum is a congenital abnormality of unclear etiology that occurs in roughly 1 out of every 400 births. The typical progression of pectus excavatum begins with minimal to no symptoms during childhood with increasing symptoms as patients reach adolescence and become more active in sports. Dyspnea with exercise, easy fatigability, and decreased stamina and endurance are common complaints.1

Physical exam is usually notable for a male patient with a tall and athletic body habitus and a slouching posture. There is a decreased anteroposterior diameter of the chest with an anterior chest wall concavity. Approximately half of these are asymmetric with the deeper portion of the concavity on the right and the sternum rotated posteriorly on the right. Tachycardia and diminished chest wall excursion may be noted as well, secondary to the restrictive defect caused by the thoracic abnormality.1

The evaluation of the pectus excavatum patient is done by characterizing the severity of the deformity and assessing for any secondary cardiopulmonary consequences. The severity is best shown by full inspiration CT and can be defined using the Haller severity index (also called pectus severity index – PSI), which is calculated by dividing the inner width of the chest at its widest point by the distance between the posterior surface of the sternum and the anterior surface of the spine.1 Normal PSI is <=2.5. From the measurements taken from the image below, this patient’s Haller index was 4.3. CT also has the advantage of showing the presence of cardiac compression and displacement.

Cardiopulmonary evaluation involves using echocardiography to evaluate for right atrial and ventricular compression, presence of mitral valve prolapse, and stroke volume which can be compromised. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing may also be useful and can demonstrate decreased VO2 max due to reduced stroke volume. Pulmonary function testing can show decreased expiratory airflow and lung volumes as a result of compression of the thoracic cavity and poor expansion of the chest wall.2

During the evaluation of pectus excavatum, it is also important to consider any co-existing processes or conditions that may be present. Two of note are primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) and pulmonary non-tuberculosis mycobacterial (PNTM) disease as there is an increased occurrence of pectus excavatum in both.3,4

Surgical management is indicated when 2 or more of the following apply:

- Chest CT showing cardiac and/or pulmonary compression, and a CT index of ≥3.25.

- Cardiology evaluation shows cardiac and/or pulmonary compression, displacement, mitral valve prolapse, murmurs, or conduction abnormalities.

- Pulmonary function testing shows restrictive and/or obstructive lung disease.

- Failure of a previous repair.2

Two popular surgical treatments are the highly modified “open” Ravitch repair (HMRR) and the minimally invasive technique for repair of PE (MIRPE) described by Nuss. With the HMRR, abnormal costochondral cartilages are removed, and the sternum is fixated with a metal strut so that the chest has a near-normal contour. The MIRPE forgoes any cartilage resection and sternal osteotomy by placing a preformed convex bar through bilateral incisions so that it lies under the sternum. This bar is then turned over so that the concavity is facing posteriorly, which raises the sternum and anterior chest wall to the desired position. Both techniques lead to improvement in exercise tolerance, stamina, endurance and quality of life.1 The long-term success rate 1 year after bar removal in 903 patients who underwent primary Nuss procedure (MIRPE) was excellent or good in 96.6% of cases.5

This patient was referred for the Nuss procedure with improvement of symptoms 1 year later.

References:

-

Fonkalsrud EW. Current Management of Pectus Excavatum. World Journal of Surgery 2003; 27: 502-508.

-

Kelly RE. Pectus excavatum: historical background, clinical picture, preoperative evaluation and criteria for operation. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery 2008; 17: 181-193.

-

Knowles MR, Daniels LA, Davis SD, Zariwala MA, Leigh MW. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia: Recent Advances in Diagnostics, Genetics, and Characterization of Clinical Disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2013; 188: 913-922.

-

Kim RD, Greenberg DE, Ehrmantraut ME, Guide SV, Ding L, Shea Y, Brown MR, Chernick M, Steagall WK, Glasgow CG, et al. Pulmonary Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease: Prospective Study of a Distinct Preexisting Syndrome. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2008; 178: 1066-1074.

-

Nuss D, Kelly RE. Indications and Technique of Nuss Procedure for Pectus Excavatum. Thoracic Surgery Clinics 2010; 20: 583-597.